As of the second week of November in 2023, there was only one YouTube comment on a talk, “Brymo, Cultural Neo Traditionalism and Postcolonial Aesthetics” given by the Nigerian scholar Adeshina Afolayan. Posted on Emory Institute of African Studies’ official YouTube page, this comment illustrates the unrelenting thoughtlessness with which social media is used around the world. For some inexplicable reason, for example, around the same time as the comment to the Brymo lecture, the UK Guardian deleted a published version of Osama Bin Ladin’s “Letter to America” after some TikTokers discovered it and essentially ran with it to justify their condemnation of the US’s cosiness with Israel and the latter’s injustices in Gaza.

While anyone might overlook the normal frenzied desire for user engagements that motivates the sensational labors of online content creators, it is the mindless redemption of Bin Laden you may find most irksome. More perplexing is also the reasoning that even if it harms civilians, terrorism could become recruitable as a legitimate form of resistance to a dominant system.

If you are a teacher of popular culture like me, you might frown at any elitist dismissal of TikTok cultures as always already juvenile and prone to algorithmic manipulations. However, we might be able to agree that college professors in the United States need to be more pedagogically committed to keeping their powder dry with regard to the state of critical thinking skills among our students. Their country’s complicity in the Middle East is well documented and they certainly do not require an infamous missive posted without the proper context on TikTok to condemn its violent history.

Yet the thoughtlessness of the social media age is not something you find only among American Gen Zers and millennials; if you look well enough, you can easily spot it anywhere the fecundity of the mind surrenders impishly to the power of thumbs clacking away on the boards and screen worlds of platform capitalism. Like the online supporters of the Nigerian musician whose celebrity outweighed the facts of his dreadful misreading of a philosopher’s essay. Here is the actual story after all that digression: let us get back to it.

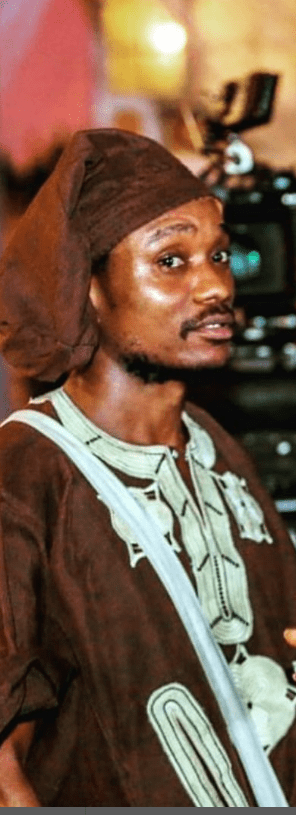

It so happened that Afolayan, an African philosopher who at the time was a fellow at the National Humanities Center in Durham, had been invited to give a talk at Emory, and he opted to speak about the work of Nigerian singer and songwriter Olawale Ibrahim Ashimi (stage name, Brymo). If you recall Biyi Bandele’s Netflix adaptation of Wole Soyinka’s historical drama “Death and the King’s Horseman,” you may have encountered Brymo in the role of the Praise Singer to the king’s horseman— a hedonistic chief whose duty to his community and a departed king is undermined by the failures of personal weakness.

In addition to the merits of his many works, Brymo’s commanding role as Olohun-Iyo is a tribute to the performer’s salt-like voice which, as Soyinka might agree, often belongs to the best praise singers and bards of some Nigerian royal courts. In both Afolayan’s essay and the Emory presentation, he analyzes Brymo’s Yorùbá songs to unpack how the musician’s songs exemplify the social and political value of aesthetics in postcolonial Nigeria. In the YouTube video, what one sees of the reception of the talk by those in the lecture room suggests Afolayan’s talk was very well received, a fact that speaks to his solid expertise in the intersections of philosophy and popular cultures.

As I understand what transpired later, Brymo got to know about Afolayan’s talk and rather than become flattered by Afolayan’s seemingly celebratory even if critical gesture towards his music, the matter became a social media contestation over one of the most influential theoretical formulations in French literary criticism, from the essay “The Death of the Author.”

Written by the semiotician and critic Roland Barthes in 1968, the concept gets to the core of textual interpretations, asking us to consider whether meaning-making derives from an author’s intentions or a reader’s interpretative power and affordances. For Barthes and other French thinkers working in his generation’s post-structuralist tradition, there is nothing outside of the text, no outside textual authority to dictate the parameters of meaning for readers. This was one of the theoretical anchors of an essay in which Afolayan similarly engages other ideas including Kwame Appiah’s postcolonial reading of the famous artwork Yoruba Man with a Bicycle, a sculpture that also fascinated the novelist James Baldwin at some point.

The age of high theory may be long gone, but Afolayan decisively relied on a reading of Brymo’s songs that imagined the symbolic death of the musician as the necessary removal of the writing body (or the performer, in this case) from the original point of enunciation. As Barthes argues, to give “a text an author is to impose a limit on that text.” But Brymo would have none of this, as he came down heavily in a Twitter (X) broadcast on his fellow Nigerian, claiming the Emory lecture “attempted negotiating my fate, and to foist on me a legacy for the price of an early demise.” In other words, Brymo incorrectly interpreted Afolayan’s theoretical reference to Barthes as an assumption of an actual death. He saw Afolayan’s Emory presentation as one of those attempts where “someone wishes me dead.” The musician probably has real enemies, especially after he went viral during Nigeria’s last elections for what many people saw as prejudicial remarks against a particular ethnic group in Nigeria.

In an industry where the fans of rival Afrobeats singers have declared him ‘dead’ in many ways, his refusal of death of any kind is understandable. But, again, this resistance to a death reference in an otherwise benign academic essay may be read as an anxiety over irrelevance in the music industry. And if there’s such an anxiety, Afolayan’s intellectual effort was a kind of symbolic resurrection that was disparaged by the ego.

As I poured over WhatsApp messages and Twitter comments mainly by Brymo and his followers, it became clear that Afolayan had been misread and his private attempts to correct an artist who cared little for literary theory would prove abortive. Even when Afolayan, as the scholar tells me, sent him messages to clarify the matter, they were met with hubristic indifference. Indeed, Brymo doubled down on his mistranslation of the essay and saw Afolayan’s attempt to explain he had not bothered about interviewing him because of the assumed Barthesian logic, this was read explained away as gaslighting.

In the world of celebrity culture, Brymo’s argument naturally wins the day, producing another nail in the coffin of whatever remains of high theory. But how do you make concepts like Barthes’s legible to a social media audience that refuses to think, or an online multitude that resurrects and rehabilitates someone like Bin Laden? Even if I say so, that question indexes troubling attitudes to knowledge in online spaces. To Brymo’s Nigerian fans, the musician, rather than the teacher, was naturally more credible, something we find in that lone comment on YouTube, as the writer unequivocally asked: “why will you assume a living man is dead because you don’t have access to him?” Another Twitter fan of Brymo’s thought the Emory lecture was “insightful [but] I feel the Prof should have contacted the artist to actually understand his art. The reference to the artist as “dead” is outrageous! In this, the outrage culture of social media dutifully manifests itself. Afolayan is lucky not to be cancelled, a fate that could have befallen him had he the influence and social capital of Brymo himself.

Like Brymo, some of these fans probably knew nothing about Barthes until their Afolayan encounter, but not even Google could redeem their ignorance. Brymo, who is expected to speak at one of the most prestigious literary festivals in Africa – the Aké Arts and Book Festival founded by writer Lola Shoneyin, ought to know better than attack a scholar who generously places his sonic art at the center of critical reflections. I may not be able to hide my love for his music, but I cannot justify the refusal to learn and think, not after your main interlocutor points you in the direction of materials to update your knowledge. In an age of information surfeit on the internet, the paradoxical surplus of closed minds has to be alarming.

At the same time, beyond the imperfections of celebrity culture and the thoughtless production of cultural content on social media, we cannot miss what the whole episode signifies for the very nature of authorship and reading practices. In the age of social media, a little learning is easily inflated, and the expertise of established voices is easily impugned especially by those who refuse to think. The production of culture in the hands of unthinking readers has to be precarious.